You’ve never heard of it before, but there’s an enlightening way to read Moby-Dick or any other work of literature. It’s a very simple exegetical magic trick, and I’m here to tell you what it is.

All you have to do is read the book as though you are the main character and everything in the book is an aspect of you, the reader. That’s not too hard, is it?

I’ll give a few examples to help illustrate, starting with the book of Job. We’ll pick Job to be the main character. After all, the book is titled Job, right? We could pick the author, but no one knows who the hell the author of Job was. In the beginning (not to plagiarize a pretty good first line), God is your (Job’s) reassuring voice, telling you how good you are and that everything is OK. The world and everything in it is all yours. Satan is that nettlesome voice saying, “But what if I’m not so good? What if I lose everything? What if I have to die?” And the messenger is your voice saying the same thing, that all will be lost. It’s the voice that you first heard when you were about 5 years old, in the dawning realization that everything and everyone you love and hold dear, including yourself, is going to have to go in the end. Fukity bye! Tempted by your own satanic thoughts, you suffer on your mind-made ash heap, covered with mind-made sores.

“Curse God and die!” says your frustrated wifely you. Why not just kill yourself to get out of this horrible mess with the loss and the sores and the ashes. “Kill yourself!” It’s not a bad idea, actually. But you don’t give up that easily. You want a reckoning with the agent responsible for your suffering, having forgotten that it’s you.

You whine and complain and carry on at the injustice of it all. To make matters worse, you have three internal devil-friends who tempt you to reduce everything to some kind of cheap moral equivalence, that there is cause and effect, and that bad things happen to good people because, really, they aren’t all that good. You must have done something to deserve your misery. Do you recognize these voices of conventional morality inside your own head?

But still you don’t give up: you insist on confronting your tormentor who, we have already stipulated, is none other than yourself. Who else could he be? For you and Job to understand the situation you are in, it has to be held in your mind. It can’t really exist anywhere else. No mind, no situation. It’s all you. And there is no mind, either. It’s the first figment of all other figments.

Elihu, the fourth and youngest friend, is the voice in your head that says, “Who the hell are you to challenge the ‘thusness’ of the ways of the Almighty? What’s the matter with you? You’re rebelling, and rebellion against the Vast Unsearchable is, itself, reason for indictment no matter how good you think you are!” Your Elihu-voice prepares you for a much vaster perspective than even “the greatest of all the men of the east,” a perspective that transcends ideas of right, wrong, and conventional justice. Something bigger is going on here. Your Elihu-self is preparing you for god-consciousness.

So your younger self-satisfied baby God and younger doubting Satan grow up. You get to have a breakthrough as the immense scope of your own mind is revealed to you. You essentially answer yourself, out of a whirlwind and rant of a mighty consciousness shift:

“Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge?”

“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?

Declare, if thou hast understanding.”

Job’s answers to God’s “who is this?” and “where were you?” have to be: “I have always been You. I have always been right here. I created Leviathan by thinking him into existence.” Where are the images listed by Job’s creator voice – the foundations of the earth, the stars, the clouds, the sea, and the rest? Where is God, for that matter? They can only exist in the mind of Job, which is to say you, the reader. Job is long gone, if he ever existed. The only consciousness is yours, sitting there reading holy writ.

If you take this seriously, your mind is now completely blown. Right?

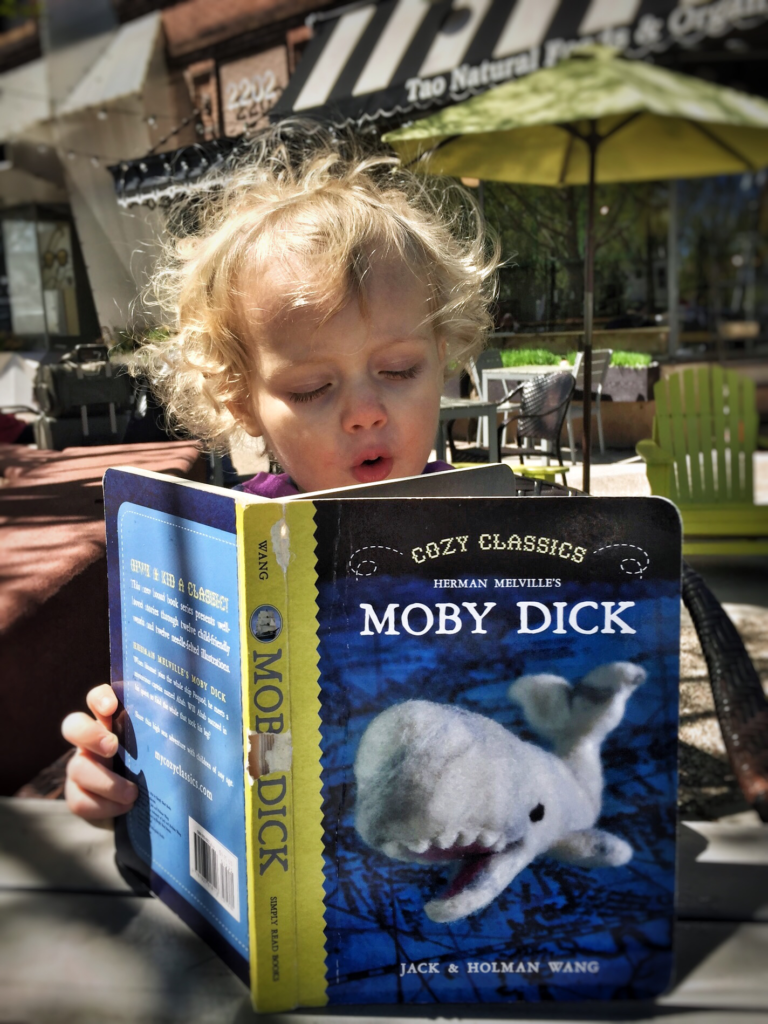

After a little rest and meditation, due to the disturbance caused by quoting the Bible and diving into it using my new fancy exegetical device, perhaps you’d like to try the device with Moby-Dick. You are Ishmael relating a voyage you take through stages of consciousness. When you are Stubb, you’re an infant with a bottle or, in Stubb’s case, with a pipe in your mouth. Older and more mature, you are Starbuck, a person who does his job courageously, takes care of his family, and obeys his god. Becoming dissatisfied with the world of conventional order, you start poking around in books and consorting with outsiders, who might hold more satisfying answers to life’s bigger questions than you ever considered before. You become the wandering outcast, Ishmael.

It becomes clear, seen in a certain way, that everyday life is an illusory prison formed of your own thoughts, perceptions, and projections. If you decide to escape, you become Ahab, determined to break through the prison walls any way you can. You, as Ahab, and you, as Moby Dick, the projected self of the universe, vanish. You disappear into the unconfined and empty truth, which you’ve never really left and which you always were. Where would you go? Returning once again to the conventional and illusory world of things, you are free to put on the costume of a messenger to report on your findings and call yourself Ishmael, if you like.

For a final example, you can read Bartleby, the Scrivener. In this story you are the narrator, a lawyer who works on Wall Street. Like Starbuck, you are successful at your work. You concentrate on doing the job well and making a good living. A part of you, though, is a little discontent. You start out with good intentions every morning, but you have to numb your doubts about work and life by imbibing too much at lunch, ruining the rest of the day. You are Turkey. The next morning, miserable and hungover at first, you start to feel guilty and redouble your dedication to employment in the afternoon. Worried that you will be found out, you even work overtime. You are Nippers. You are also the young lad, Ginger Nut, whose job is to distract you from the misery of your existence by the superficial diversions of cakes and ale, symbols that Melville uses for the empty calories of trivial romance fiction.

Things get worse, though. The Bartleby-you does the work very well, but cannot abide it even as well as Turkey or Nippers. You try to protect this most functional part of yourself by walling it off behind a screen separate from the suffering corners of your consciousness, hoping to keep doing a good job making copies of copies as a kind of miserable Platonic legal artist. One window of the office opens on the white wall of a shaft, and the opposite onto a black brick wall. Bartleby himself looks out a side window “with no view at all.”

Eventually you quit copying anything and gaze ceaselessly out the viewless window. You, as owner of the business, try to get rid of Bartleby, but you can’t. You can’t get rid of you! You eventually try moving away from yourself, but remember, using this technique everything in the story is part of you, including your office. Eventually, you are moved from the prison of your old office to your new prison called “the Tombs.” You realize that you are a living letter stuck in an envelope with no forwarding address and no return address, trapped in the dead letter office.

On Wall Street, staring at the walls; in the Tombs, staring at the walls; and in the dead letter office, staring at the walls; you are trying to discover a way out of the prison called reality, and you do. Your Bartleby self dies to your conventional self, and is freed.

Teachers and professors commonly advise that you don’t drag your personal story into the story you are reading. This is helpful advice particularly if you are discussing it with others since you’ll have to tell your whole story in order for them to have the new context, which destroys the opportunity to understand the story that you’re reading in the first place. The same is true if you’re reading the story alone. If you bring your own story into the context of the story, pretty soon you’ll have stories on top of stories with nothing to show for it.

Instead of putting your story in the context of the story you are reading, it is important for you to put you in the context of the story. Don’t drag your weird Uncle Fred, your cheating boyfriend, your tyrannical boss, and your insane night-school professor into it!

As you practice with the exegetical magic trick, you will begin to expand your perspective on life. Perspective means to see through, like seeing through a lens or through a certain point of view. Taking the point of view of each person and object in a story expands the number and scope of perspectives through which you see the world. With certain kinds of literature you are even able to adopt the universal perspective of god-consciousness, which sees all.

And yet this still is not the end of the journey. Ultimately, you transcend all perspectives in the realization that there is no one to have a perspective. There’s no one to do any seeing, nothing to be seen, and nothing to see through in the first place. You are the hero on the hero’s journey of exile and return, and you’ve ascended (or descended) through a series of stages of consciousness. Then comes the dazzling realization that there are no true stories to begin with, and you step off the stage altogether.

Each character and object in a book, movie, or play are only you in disguise. This includes the story called your life. God, Satan, and Leviathan are just you playing roles. So are Turkey, Nippers, Ginger Nut, and Bartleby; Stubb, Starbuck, Ishmael, and Ahab; and Uncle Fred, your boyfriend, your boss, and your instructor. They are versions of you at different stages of consciousness, so be nice to them.

At the end of the story, Job, Ishmael, and the narrator in Bartleby end up in the same place they’ve always been and you end up in the same place you’ve always been: nowhere. And who are you, wearing all these disguises? You are Brahman. You are God, silly, before he said, “Let there be light.”

Wow. That was fun. I’m still at Turkey level.

What do you make of the ending of BTS?

I think most individuals can acknowledge the idea of nothing existing except that the mind imagines it, but the plunge into the other is tough to comprehend.

One more thing: If I teach a short story class (using BTS BTW) at a corrections institution every Monday evening next semester, do I get extra credit?

Of course you do. Extra credit for the irony.